Blog

Influences: Oor Wullie

30th December 2014

Dungarees, tackety boots, and comedy fundamentals.In a book sale this year I found some classic collections of Oor Wullie. These normally attract collectors’ prices but in this case were cheap, perhaps because the pages were falling out and several had been coloured in by some Falkirk child of times past. And not by carefully selecting an appropriate colour and filling the area between the lines either — said child had simply picked a page and scrubbed with a purple crayon until becoming bored and selecting a page from the next book.

Oor Wullie will have featured in most Scottish childhoods. This comic appears weekly in the Sunday Post, a gentle tabloid still published by Dundee’s D.C. Thompson. I recommend the paper on a Sunday morning when you are feeling particularly delicate, and need to be insulated from any actual news. On the other hand, if you need one extra ball of wool in a discontinued shade, its readers’ page is a better bet than eBay.

As you grow up, you naturally gravitate to the more adult concerns of its sister strip, The Broons, an unfeasibly large family of comedic archetypes who still live together and are regularly flummoxed by the antics of their spry grandfather. But as a boy I was concerned with the adventures of Oor Wullie. (That’s “Our William” in English.)

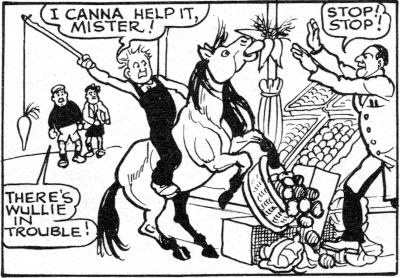

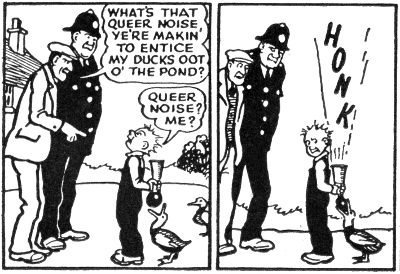

Wullie is a mop-headed youth who has some strange preferences: he only likes to wear black dungarees and always sits on a bucket to philosophise. He is often in trouble with his parents, teachers or even the law, but he is not a bad lad at heart; just prone to unfortunate coincidences or thoughtless accidents. In a typical Oor Wullie story, he refuses to play draughts with his cousin Agnes, but opts to explore an old warehouse, ripping his dungarees on the broken window. Patched up, he returns to do daring leaps onto a mattress, but overshoots and lands in a basin of oil. Cleaned up, he returns to play headers in the street but clobbers his skull against a lamppost. Finally listening to his long-suffering mother, he plays draughts with floppy-bow-haired Agnes — who promptly punches him in the face for cheating.

The rhythms of Oor Wullie were good source material for structuring the comedy that I now write. PC McMurdo from Neighbourhood Necromancer is a harder version of Wullie’s benevolent nemesis PC Murdoch. Telling a self-contained funny story in a single page, and doing it week after week — the classic writer/artist team R.D. Low and Dudley D. Watkins did both strips in addition to other work — is not as easy as it might seem.

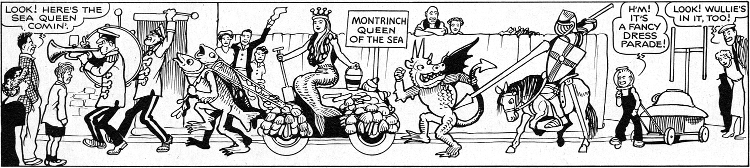

But what caught my imagination were the bizarre adventures that Wullie has in what is a very ordinary wee Scottish town. Asked by three separate people to deliver a goldfish bowl, a large aerial and a giant promotional teacup and saucer, he ends up winning a fancy dress competition as a “flying saucer man”.

Wullie is not particularly concerned with material things, beyond the latest issue of his favoured comics (coincidentally also published by D.C. Thompson) and perhaps the odd apple or bag of sweets. When his best pal Fat Bob lords it over him with his new pedal car, Wullie constructs his own from an upturned bath. It appears self-powered until the top comes off and he is revealed to have been exercising somebody else's dog all this time, no doubt for a 10p tip at the end.

He is also fond of repurposing objects. When he inherits PC Murdoch’s bearskin hat, he uses it to assist a lady with her shopping, catch a plummeting pot plant and replace a horse’s leaking nosebag. When forced to learn violin, he uses it to swat back divots hurled by a rival gang, and as a bow to shoot sticks. A builder’s hod saves a large gentleman from falling down a manhole, keeps mince away from hungry dogs, traps a rabbit and provides an impromptu elevated chair at the football match. His beloved bucket serves as many things: central heating, armour, lampshade and a watering device for lettuce.

Wullie’s world is one of simple problems and mishaps which are generally resolved by the end of the page. But I still enjoy the imaginative scrapes he gets into with everyday things, and I now recognise these as the foundation for much of my sense of humour.

Sterne und Autobahnen

27th Dec 2013

Reflections on managing a creative process.2013 has been my busiest year of writing ever, and it has included multiple collaborative projects. I really enjoy collaboration, particularly the early stages. At that point it’s all about the ideas, and the project is taking a shape that is (hopefully) stronger than any individual would have devised on their own. Here's some thoughts on the process.

The Director

Where there’s only two of you — such as in the project Dread Code, which is going to hit you in a nerve cluster when Ali Maloney and I finally get it out the door — it’s all about the relationship between you. Respect and honesty are the qualities which make that work.

Once you get beyond two people, somebody has to be in charge. Call them the director, call them Grand High Pooh-bah; you need somebody who ultimately makes the final decisions. My regular mob Writers’ Bloc is a collective, but the group understands itself well enough to appoint a director for every show it does. This year I got to be in charge for the Edinburgh International Book Festival show with John Lemke and Poppy Ackroyd.

Managing a collaboration is all about balance. You need drive, because that initial burst of enthusiasm will not carry your group all the way to the finish line. You need vision, because everybody will see the project in a slightly different way, and you are the one that has to bring them together in harmony. And you really, really, need good people skills, because creative people can be egotistical and temperamental, and you may need to get through that to reach the point where the brilliant work emerges. That includes being able to say “no” without flinching.

You also — and this can be the hardest part — have to accept that other people’s ideas may be better than yours, and if the group agrees, you have to be willing to give in.

The Process

Perhaps you are working within an existing structure and the rules are set. Season 8 of Star Trek: The Next Generation would impose a lot of restrictions on your writing team. But if you’re creating something from scratch, particularly if you’re not paying professional rates, you owe your collaborators a piece of the fun that comes with raw creation.

On the Book Festival show, we were challenged to create stories around John and Poppy’s debut albums: People Do and Escapement. We got hold of the albums and listened to them on repeat for a week or two. Then we got together over a pint to make creative decisions. It surprised me when people said, “Just tell me what to go and write.” That seemed to miss out the best bit: coming up with an assortment of incompatible, messy ideas, and wrestling them into a workable and powerful shape. I was determined to consider all suggestions at first, and narrow the focus as the weeks progressed towards the event.

The easy thing to do, of course, was to let individual writers respond to individual tracks any way they wanted. We could have assembled a programme of random short pieces to accompany the music. Some people were keen to take this route. This was the first time I exerted directorial authority; it seemed to me that this was a special event and a single, multi-author story would be more powerful. Of course, creating it would require more structure.

What struck us about John’s music was its constant movement and European flavour. Poppy’s music seemed more introspective, more passionate. We took these qualities as the basis for two characters who would meet and fall for each other. The man was a fixer for Euro high society, procuring rare goods irrespective of borders or legality. The woman was an academic, a researcher, looking for a way to make a difference; for her true place in the world. He would sweep her off into a world of motion and glamour, and her commitment to change society for the better would eventually break them apart.

I was happy with this central conflict and the narrative it suggested. But a couple of writers hated the idea that the man was the active one and the woman effectively wanted to settle down. Gradually an idea emerged where she would go into space and that was what would end the relationship.

I hated this initially because I saw the interaction between them as the core of the story. I felt we would end up with stories about ‘what it was like to be on a space station’ instead of stories about lovers whose values tore them apart. But the idea created enough energy that I didn’t want to step on it. So I rolled with it, specifying only that the stories should be about the relationship, not the technology.

In the end, what made the science fiction component interesting was when we nailed it as a colony mission to Mars. It made sense for our researcher to be an agriculturalist, and crucially it was a journey that could not be reversed. Once she left, they would never be together again, no matter how much they wanted to.

The Details

Once we set deadlines, the first material came in. Quickly we had too much to fit in the show. This is where the director has to make the first really tough decision: eliminating pieces which don’t fit the overall picture. And crucially, it is a picture which emerges. Regardless of what you thought you were going to get, you have to assemble a completed work from what you do get. This is the downside of keeping the concept open enough to allow the writers to put their own spin on it.

I arranged a session where the writers got to meet John and Poppy. Probably my biggest mistake in the process was to let the musicians see early drafts which would never make it into the final programme. As composers they already had an intense, intimate relationship with their music, and those tracks were already full of imagery for them. It was hard on them to accept other interpretations, especially rough scraps which hadn’t had the benefit of the workshop process and might never make it through. Ultimately we all had to get onto the same stage. I had to ask them to trust us.

From about here my iron fist emerged from the velvet glove. Some stories spent too long on tangents and had to be brought back to the theme. Some stories were too long for the time available and had to be cut down. Several got discarded entirely. I moved from general guidance to specific suggestions to, as we ran out of time, direct editing. This is where you can really upset people, but I kept the process transparent and tried to retain the character of each piece while fitting it into the overall story. Even Stuart finally agreed to soften his “and then they all died horribly” ending and provide a brief moment of hope. We were done.

The Results

The moment I knew we’d got it right was our one and only rehearsal, in a poky underground studio in Leith. It was fun fitting our narrative into the music. Poppy and John seemed much happier, and there were a couple of moments where the combination of words and music resonated very deeply. I took notes of how it all fitted together and produced a detailed running order showing every transition. On the night, I basically got to relax and enjoy it.

I recommend trying a collaboration if you haven’t before. It’s a different challenge from working in isolation, and it requires a tricky blend of negotiation, sensitivity and assertiveness. But it is also a rare pleasure.

Zombies, Run!

18th August 2012

Keeping fit with a dose of terror on the side.Lately I have been running around parks and hidden lanes in Edinburgh’s South Side. This is the first bit of running I have done since leaving high school. It wasn’t inspired by the Olympics; I wanted to play a game.

I aspire to stay fit, but like a large percentage of the population I have trouble keeping up a exercise regime. This is down to two factors: a busy, unpredictable schedule, and the fact that solo exercise is just so damn boring.

The local gym was fine for a bit. I took audio books and listened to them while I stretched, moved unimpressive stacks of weights and watched a new generation of narcissists examine themselves in the mirror. But the gym insisted on playing chart music at a volume loud enough to drown out my books, so I cancelled my subscription.

Along came a smartphone app called Zombies, Run!. This is one of those instantly brilliant ideas: it’s a game where you run, and zombies chase you. There’s more to it than that — as somebody said at the recent Edinburgh Interactive conference, “Once you’ve done one zombie chase, you’ve done them all.” It tracks your progress by GPS, maps your route, monitors your speed, interrupts your music playlists, and crucially it immerses you in an ongoing story. It’s a horror audio book you have to go running to experience.

It’s possibly not the optimal training tool; lately my monkey brain has worked out that if I run slower on average I will have more stamina when the zombie chases occur, and so my times have been getting worse while my score in the game has been improving. I think I may have to turn the chases off for a bit and play it more as a straight narrative with gaming elements.

The most interesting thing for me has been the juxtaposition of the immersive story, my playlist, and the unpredictable location. Once I was out of breath, forty zombies were after me, and my playlist switched in Cardiac Arrest by Madness. Another time I was on holiday, running a bridleway up the top of a remote hill in Oxfordshire. There was nobody to be seen for miles, I didn’t know the area at all, and my companion in the story suddenly produced a gun and became threatening. On some level I knew it was still a story, but the isolated location gave me a stronger sense of unease than any horror film watched on a familiar sofa.

Zombies, Run! is really not that interactive in a “choose your own adventure” sense. Your speed and distance affect the game elements which accompany the story, but I think you get the same audio snippets whatever happens. However it plays to the strengths of radio drama, forcing you to visualise the scene yourself. As a player, you have a completely unique reading of the story, because nobody else has the same combination of plot, music and location that you do. That level of imaginative experience gets me off the sofa.

Finding the Story

9th March 2012

Literary excavation by starlight.The process of coming up with an idea for a story is mysterious. Harlan Ellison liked to lie that he got all his ideas by post from a service in Schenectady. It’s not like Sudoku, where certain rules, rigorously applied, will always solve the problem. Yet it is something of a puzzle to be solved. I spend a lot of time on this when I’m teaching, because for many students getting started is the biggest obstacle. This is the process I used to come up with the idea for my story Starfield for Edinburgh City of Literature’s enLIGHTen project.

I got the commission email in last thing on a Friday. That weekend featured two tough deadlines, and I was teaching on the Monday evening, so I didn’t really engage with it until Tuesday. At which point I learned they wanted a piece of flash fiction by Friday, for audio delivery, to a very specific brief.

The story had to relate to David Hume’s old house, previously at 8 South St. David’s Street. It also had to be a response to a quote by the poet Allan Ramsay:

Schools polite shall lib’ral Arts display,

And make auld barb’rous Darkness fly away.

Now, understand, my normal process for writing a story includes leaving it in a drawer for two weeks, and having it workshopped at a monthly session with Writers’ Bloc. I am also absolutely dreadful at writing to themes. It’s just not how my idea factory works. I contacted Peggy at City of Literature and blagged a weekend extension to the deadline.

So now I was committed to doing this in about five days. It wouldn’t be the writing that would be the problem; 600 words is nothing. The challenge would be coming up with a workable, on-topic idea, and forcing it to come quickly. I saw three possible entry points: the location, David Hume himself, or liberal arts.

Location

I had time on Wednesday to walk down to David Hume’s house and look around. The actual pavement in front of the plaque, which is very high up for a casual observer, was dominated by black binbags and dirty phoneboxes. I shot a photo panorama, which came out distinctly uninspiring. However, I was intrigued to discover this crest on the same building, around the corner:

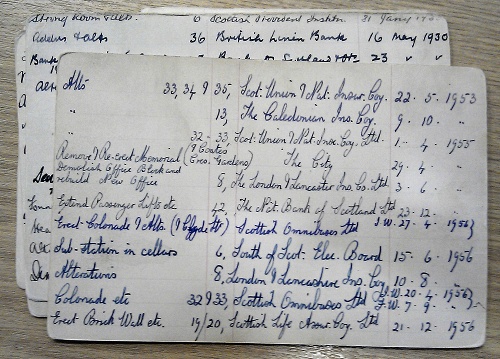

To find out more I headed to the Council’s historical planning records office on Cockburn Street. I explained what building I was interested in and was trusted with a stack of handwritten cards recording planning applications for St. Andrew Square dating back to 1861.

I could have spent literally all day digging around in these, but I had half an hour until the office closed. I followed the history of the building, number 8 St. Andrew Square. June 3rd, 1955, shows an application by The London & Lancaster Insurance Co, Ltd. to “Demolish Office Block and rebuild New Office”. Subsequent entries refer to Standard Property Investments.

I headed to the Edinburgh Room in Central Library on George IV Bridge to see if I could follow the history of the site. They had a number of photographs covering the area. After a tedious process of form-filling to request them one by one, a helpful man brought me the entire stack. I saw the Ivanhoe Hotel, just down the road, now gone; a splendid dark townhouse across the street, on the corner of Rose Street, now gone; and eventually, a two-storey clothiers named Harrison & Son, on the very spot where the plaque was. It had a two-storey residential extension on top. And yes, it was gone, presumably demolished in 1955.

Fascinating as architectural history is, none of this was really getting me anywhere. David Hume’s actual house had vanished, probably demolished around the 1890s, and the story emerging here was of aesthetically pleasing buildings being replaced by bland grey blocks. It was too generic to address the location and it didn’t refer to the Allan Ramsay quote at all.

As I was close, I popped into the City of Literature offices to say hello and show Ali and Peggy the photos I’d found. Ali recommended James Buchan’s book, Capital of the Mind, for reading on the period and Hume in particular. That was to be my next approach.

David Hume

My initial knowledge about Hume was rather pitiful. There was that statue of him on the High Street with the shiny toe, of course. But the only philosophy I had studied related to scientific models, and artificial intelligence in particular. Hume’s contribution seemed immense, too much to grasp in such a short time.

I began with Three Minute Philosophy: David Hume and worked up from there, finding a comfortable level of description in some university lecture notes. Two aspects of his thinking seemed promising for a story: his ideas on cause and effect (we never actually experience this happening, we just construct the relationship ourselves) and his ideas on self and identity (we have no mind as such; we exist only as a bundle of perceptions). By this time it was Friday lunchtime.

I'm in a poker school with a bunch of supposedly educated people. On Friday night we were crammed around the table, booze and snacks scattered across the green felt, when it occurred to me to ask if anybody was “into David Hume”. There were a few seconds of awkward silence and then the game resumed.

However, around three in the morning, Ahmed gave me a lift home. He raised the subject again and revealed he was quite the David Hume enthusiast. We talked about Hume’s ideas. Ahmed urged me strongly to read the Treatise of Human Nature. I knew I didn’t have time for that, but our chat kept things uppermost in my mind as I went to bed. I felt there were definite possibilities in Hume’s exploration of self. When our perceptions stop, we are annihilated.

Liberal Arts

By Saturday afternoon I was ready to explore the final area: liberal arts. I had a feeling this didn’t mean the same thing in Allan Ramsay’s day as it does today. I took a chance, and trusted Wikipedia.

The entry on Liberal Arts was just what I needed. The original three liberal arts were grammar, rhetoric and logic. The medieval period added mathematics, geometry, music and astronomy. I was drawn to this second list, my kind of subjects. For the first time in the process I had the feeling of being onto something; an elusive energy which as a creative person you get to recognise and pursue.

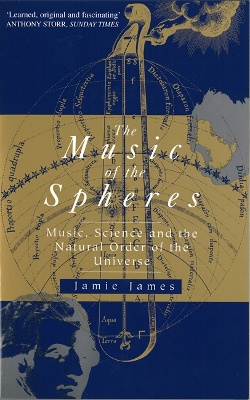

I use mind maps to force myself to think around a subject. (They’re also a good excuse to use coloured pens.) I started a mind map on liberal arts, but only managed to get down maths, music and astronomy when I had the first solid idea. CLUNK. It concerned the Music of the Spheres.

This is another ancient concept: that the movements of celestial bodies produce a kind of harmony. Not one which we can actually hear, but one expressed in terms of proportion and tone. The sun, moon and planets resonate; effectively they hum, and this has an intangible effect on our lives on Earth. Music is mathematical anyway, with harmony expressing ratios of frequency. (If anybody had explained this to me in terms of numbers when I was young, it might have saved my piano teacher, Miss Campbell, a lot of frustration.)

I grabbed Jamie James’s book on the subject, which had been at the bottom of a dusty stack for several years, and got reading about Pythagoras. I didn’t get far, because suddenly there it was, the idea. Combine Hume’s philosophy on self and perception, with this cosmic music. Tap into nighttime fears of insignificance and mortality, and offer reassurance with the omnipresent music of the universe. CLUNK again. I dare say Hume would have dismissed this reassurance … but he wasn’t my target audience.

The scene dressing was easy. The Occupy Edinburgh protest camp had just been evicted from St. Andrew Square. What better setting for existential fears than a tent on a winter night? Sleeping under the stars … and this was the final CLUNK. The structure was there. But one more thing was nagging at me.

The Stars

I remembered reading an article on sounds made from star vibrations. This endeavour combined music, astronomy, and maths, and conveniently, stars also lit up the Earth. It was a perfect fit for the enLIGHTen project.

I Googled carefully and tracked down a page of sonifications from the Kepler satellite. Listening to them, I thought some could fit behind spoken word without being a distraction. So I sent an email to NASA asking permission … and that was fun in itself. The scientist concerned, Jon Jenkins, was charming and generous. A quick examination of star charts for the proposed night; a nod to David Hume’s house in the southwest of the square … and the first draft was done by Sunday night. Adding the star sounds would come later.

That’s the trail I followed to find the story of Starfield. Feel free to read it. But I would rather you listened to it, and the sounds of the stars.

The Rising Elocutionist

29th February 2012

Happy Birthday, Molly.Today would have been the 100th birthday of my granny, Mary Fraser Anderson Young (1912–1995). She liked to be called Molly. Because of the leap year, technically it would have been her 25th birthday.

She was a fun granny. I remember little details about her. When I was very small, she would make a swing by hanging a bit of wood from hooks in her kitchen doorway. After she was widowed, she kept two pictures of Grandpa around, one rather stern and one happy after singing at a concert. She would switch them depending on how she felt she had been behaving.

Granny was … I don’t know if religious is quite the word, but she was certainly God-fearing. After I went vegetarian, she told me seriously that she believed God had put the beasts of the field on Earth “for us to eat.” It didn’t seem worth having a disagreement over.

Nevertheless she loved card games, and we often played “A Hundred Up” which is a variant of gin rummy. She also read fortunes in tea leaves, but seemed uneasy about this, like it was a bit wicked. She was horrified when she discovered my cousin had been doing the same thing to raise money at her school fair.

I had barely started doing spoken word when Granny died, and never made a connection with her about it. But I was startled, years later, to find out she had been an enthusiastic and popular turn on the church social scene for her poetry recitations in Scots.

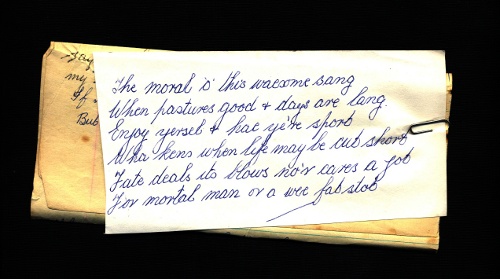

Molly had a stammer when she was young, and so went to elocution lessons. She threw off the stammer and became interested in performance. We’ve still got a folder of her material. There are a lot of scraps — she acquired material from newspapers and friends — and one yellowed Boots two hundred sheet refill pad, where we think she was collecting good versions of each poem. There’s stuff about church mice, Greenock men, the decline of shipbuilding on the Clyde, how a dog is better company than neighbours, and even a gentle nationalist jibe about the English stealing all “oor watter”.

We’ve still got a clipping from the Greenock Telegraph, sometime in the 1930s, which describes her as “Molly Young, the rising elocutionist”.

Happy birthday Gran.